Abject apologies, Gentle Reader, for my long silence. I have been busy packing my books and belongings into barrels for their journey on the Rhine. But let me continue my story from where I left it in my last post.

Abject apologies, Gentle Reader, for my long silence. I have been busy packing my books and belongings into barrels for their journey on the Rhine. But let me continue my story from where I left it in my last post.

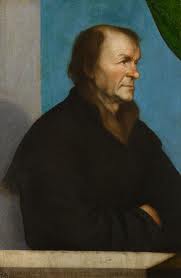

There was the sound of hooves on the cobblestones outside, and my name was shouted by a youthful voice. Looking from my upper window, I observed three horsemen dismounting. I recognized the two younger Amerbach sons. But the third man I failed to recognize, because I was not expecting an old friend with two new ones. But by the Muses! It was Fabri.

I hurried down, still without my robe and my blouse untied, though it was midmorning. They were glad to see me. Even Fabri’s reserved manner was lightened by a smile and some flickering amusement in his eyes. Bonifacius was excitedly twisting his horse’s mane. “We have great news!” he said.

I hurried down, still without my robe and my blouse untied, though it was midmorning. They were glad to see me. Even Fabri’s reserved manner was lightened by a smile and some flickering amusement in his eyes. Bonifacius was excitedly twisting his horse’s mane. “We have great news!” he said.

But his older brother, Basilius, punched his arm, scowling. “That’s Fabri’s business! Do you work for the Bishop now?”

Though Bonifacius was sobered, he looked expectantly at Fabri, who said simply, “I’m parched.”

I showed them the hospitality of my late prince-bishop’s wine cellar, and they talked of the news from Basel. Erasmus had been there a few months earlier, but now was gone.

“I wonder if I shall ever get to meet him,” I said. “His writings are light in my darkness here.”

There was a pause, as if the very globe of the world held its breath. Then Fabri slowly removed a document from his satchel and handed it to me. The red seal bore the imprint of a bishop’s crook. I carefully peeled it away rather than breaking it.

There was a pause, as if the very globe of the world held its breath. Then Fabri slowly removed a document from his satchel and handed it to me. The red seal bore the imprint of a bishop’s crook. I carefully peeled it away rather than breaking it.

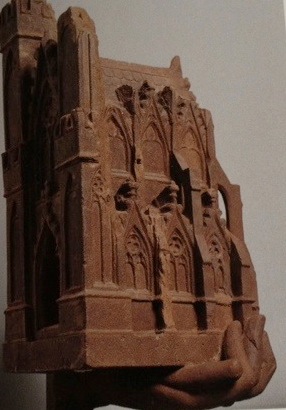

Bishop Christoph von Utenheim of Basel was offering me a position as cathedral preacher. I would also be offered a position at the University of Basel as soon as I completed the requirements for my doctorate. I read the letter three times. I could scarce take it in.

“This Bishop von Utenheim is a great advocate for good letters,” Fabri said. “He longs to bring scholars of the new learning to Basel, and I think his efforts of last winter to make Erasmus feel welcome and honoured are one reason Erasmus plans to return to Basel and have his next works printed there. The Bishop is also a sincere advocate of ecclesiastical reform, having been asked by the abbot of Cluny to reform the monastery of St. Alban at Basel.”

“This Bishop von Utenheim is a great advocate for good letters,” Fabri said. “He longs to bring scholars of the new learning to Basel, and I think his efforts of last winter to make Erasmus feel welcome and honoured are one reason Erasmus plans to return to Basel and have his next works printed there. The Bishop is also a sincere advocate of ecclesiastical reform, having been asked by the abbot of Cluny to reform the monastery of St. Alban at Basel.”

“Not that the monks wish to be reformed,” Bonifacius laughed, and Basilius frowned at him.

I reread the letter. It was difficult for me to swallow. “This is your doing,” I said finally to Fabri. “You are my savior.”

“No,” Fabri said. “Your friend, Pellicanus, suggested you for the post. I only stood as witness to your talents when the Bishop asked me. And the Amerbachs have added their voices to the hue and cry for Capito.”

Now Basilius Amerbach spoke. Unlike his brothers, he was so soft-spoken that I had to listen carefully. “You know, Master Capito, that our father went to God with his most ambitious project still unfinished.”

The monumental Complete Works of Jerome, which the elder Amerbach had discussed with me when I first visited his home. He had predicted then that it would run to ten volumes, and that he would not live to see it completed.

The monumental Complete Works of Jerome, which the elder Amerbach had discussed with me when I first visited his home. He had predicted then that it would run to ten volumes, and that he would not live to see it completed.

“Our grief is further deepened,” Basilius said, “by the death of Johannes Cono, my father’s trusted advisor in Greek. The Jew, Adrianus, has left us as well.”

He sighed. “Let us speak the honest, simple truth, as one German to another. Of course, we are thrilled that Erasmus has decided to combine his efforts on Jerome with those of our own. His name alone will help to make it a successful financial venture, and not just a labor of love, as were so many of my father’s projects, for you know, he always wanted to produce works of great beauty and spared no expense on types and illustrations.

“But Erasmus has huge plans for Jerome. Plans that. . .” again Basilius hesitated, “plans that are beyond the abilities of one man even with the assistants that he often calls upon. Erasmus, himself, declares he is woefully deficient in Hebrew studies.”

“But Erasmus has huge plans for Jerome. Plans that. . .” again Basilius hesitated, “plans that are beyond the abilities of one man even with the assistants that he often calls upon. Erasmus, himself, declares he is woefully deficient in Hebrew studies.”

At last the younger Bonifacius could contain himself no longer. “Erasmus wants the Jerome to have introductions, antidotes, commentaries, word studies. He sees it as nine volumes with 4000 scholia.”

I nodded. Scholia, marginal commentary on history or etymology, would be extensive in a work that dated to the fifth century, contained several languages, and was based on multiple manuscripts.

Again Basilius spoke, “Even more important, Erasmus will also be working on his New Testament, which Froben will print this winter. You know, we have a great fondness for our father’s friend and assistant, Johann Froben. He is an excellent printer, but he is not an educated man.”

Again Basilius spoke, “Even more important, Erasmus will also be working on his New Testament, which Froben will print this winter. You know, we have a great fondness for our father’s friend and assistant, Johann Froben. He is an excellent printer, but he is not an educated man.”

“Erasmus calls him stupid,” Bonifacius said, for which he received yet another glare from his brother.

“That had more to do with the problems of his household and his trusting nature,” Basilius said. “We need your help, Capito. Please accept the Bishop’s offer and move to Basel. Put your shoulder to the wheel beside ours to assist Erasmus with his great projects, which will benefit all men who love piety and good letters.”

I sighed to release the pressure of my feelings. “I get to preach Christ truly, help a reform-minded Bishop, teach at the University, and work at a printer’s with some of the greatest scholars in the German lands.” Once again, I choked back tears of gratitude. “You honor me far too much, my friends, who want to put a pack saddle on an ox. But this ox promises to do his best.”

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Rhine riverboat from German Waterways in 1632, Detlef Zander.

Froben edition of Jerome located in the Gdansk Library of the Polish Academy of Science.

←Previous Next→

Comments most Welcome via the tiny word below.